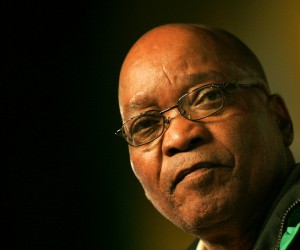

President Jacob Zuma, who acknowledged a serious problem of unemployment among South African youth at a Japanese investment conference on Africa, said the government was considering a “revised youth employment incentive” to tackle the problem that affected about half of young people.

The comments at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (Ticad) were the first signal in months that the government now appears to be forging ahead with the incentive.

This is despite fierce opposition from the ANC’s alliance partner, Cosatu, to the plan to implement the incentive system, which was first proposed three years ago by Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan.

Zuma later said there had been concerns in union circles that the plan would cause a loss of jobs, but he believed the social partners, including labour and business, were on board following the signing of an employment charter.

The labour movement has criticised the scheme on the grounds that older workers would be phased out of the market place to accommodate new entrants who would cost companies less.

South Africa has an unemployment rate of more than 25% and many economists say incentives could start to address the problem. Moreover, they argue union demands for uneconomic wage hikes make the situation worse.

Investment Solutions' chief strategist Chris Hart said Zuma’s comments revealed an “undercurrent of unilateralism”, a determination to press ahead with policies that could produce tangible results ahead of an election year.

Speaking at a panel discussion on youth and employment in Africa titled “Empowering Young Africans to Live Their Dreams”, Zuma said the government recognised the country had an urbanising and youthful population “that bears the brunt of unemployment”. He pointed out that most of them were black.

Taking part in the discussion were Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete, African Development Bank president Donald Kaberuka, World Bank Group president Jim Yong Kim and Gabon President Ali Bongo Ondimba.

Zuma said unions in South Africa had achieved much during the years of democracy, but there remained two economies in the country. A large portion of the population fell outside of the main economy and did not even benefit from minimum wages because they were unemployed. There was also the historical legacy left by apartheid, which had a negative impact on the lives of young people in particular.

One of the ways of addressing this challenge was to transform the economy through reducing the concentration of economic ownership in the hands of “a small section of our society” Zuma said.

It was also imperative that African governments placed skills development “at the centre of our strategy”.

Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe said although some strides had been made in African economic development of late it remained “quite clear to us that most of us are still at a primary economic level”.

Many African economies were still involved in “the extractive industry”, in other words mining for resources, Mugabe said. Japan should be ready to assist Africa “in industrialising”, Mugabe said.

At the panel discussion, Kikwete said growth in Africa in the future had to be “pro-poor” and “pro-employment”. If youth unemployment was not resolved, it had revolutionary potential, he warned.

Kaberuka said poorer countries were held back economically by poor infrastructure, while middle-income countries like South Africa tended to be held back by poor or ineffective education systems. Different countries had to adopt different strategies to fight unemployment, but these issues needed to be tackled first.